To celebrate Mental Health Awareness Week, JJ Buckle soaks up the research on how nature can boost wellbeing.

JJ Buckle

When you think of bathing, what comes to mind? Perhaps a bubble bath, scents of lavender encircling you as you ease back, close your eyes and relax? Or lying in the sun, the rays washing over you, warming your skin and providing a deep sense of tranquillity?

But how about bathing in a forest?

A practice which originated in Japan, known as Shinrin Yoku, forest bathing centres around mindfulness whilst surrounded by trees and nature.

Studies have shown that participants (particularly those experiencing mental health problems like anxiety and depression) showed significant increases in mood after a forest bathing session, as well as improvements in physiological factors (blood pressure and pulse rate).

This is an example of nature- or eco-therapy, and it isn’t a new concept. In the 6th century BC, Cyrus the Great is said to have built relaxation gardens in the middle of the bustling Persian capital to improve his subjects’ health.

The art of healing comes from nature, not from the physician.

Paracelsus, 16th century AD

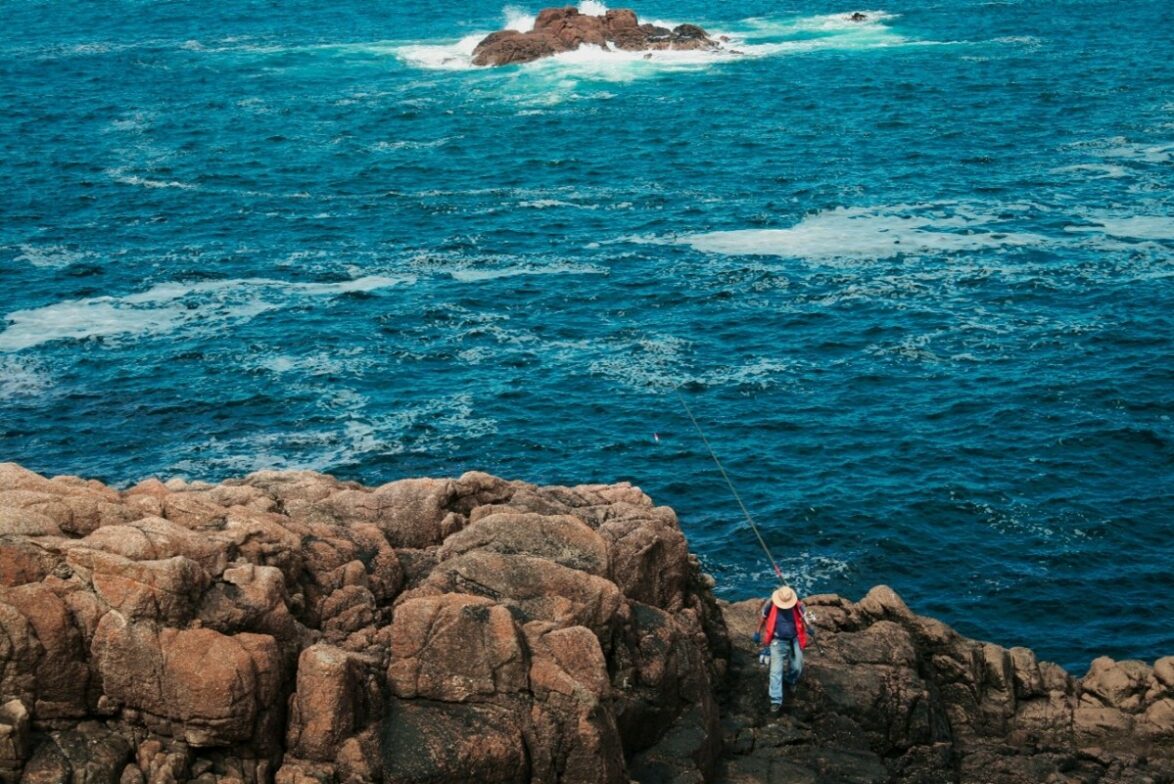

Whilst I have never been prescribed a course of Shinrin Yoku, or engaged in a forest bathing session, I definitely notice a certain calmness when I am next to the ocean with the waves lapping at the shore, or sitting in a sunny London park watching the birds flutter from tree to tree. Nature has a profound calming effect on me.

In this, I know that I am not alone. ‘Nature’ is the theme of this year’s Mental Health Awareness Week, and you only have to google ‘nature and mental health’ to see a plethora of articles and posts from large mental health organisations espousing the importance of nature in our mental wellbeing.

Growing understanding

Direct benefits to our mental health will differ from person to person. The chirping of wrens in the morning puts me in a good mood and helps me feel connected to my environment.

Others might find this early morning noise annoying. Likewise, some people feel stressed in high temperatures, whereas others’ moods seemingly rise alongside the mercury. What seemed more universal was that during lockdown many people relied on their daily time outdoors to provide a brief respite and a chance to decompress.

While personal preferences do come into it, there is a growing body of evidence which indicates that having access to, and enjoying, nature can benefit a person’s mental wellbeing. Research has indicated that these benefits can occur across the entire spectrum of mental health – those without mental health issues benefit from experiencing nature, just as people with depression or psychosis do.

And there are also the physiological impacts.

Studies have reported that access to natural environments decreases the likelihood of people reporting insufficient sleep and helps regulate circadian rhythms.

Being outside provides opportunity for exercise, activity or movement and social cohesion. And, depending on where you are (and when), time outdoors can correspond to an increase in exposure to sunlight.

All of these generally correspond with lower levels of mental health issues, or are considered good additional treatments for mental health problems. A recent study even found that naturally occurring lithium in drinking water can reduce the number of suicides in the population exposed to it.

There are some fascinating and novel studies out there about how aspects of the natural world can impact our mental health.

Wild nature

Nature at its purest inspires and excites me. When I watch camera trap footage of snow leopards stalking through the Himalayas, or see video of condors soaring through the skies over the mountains of Peru, I am in awe at the majesty of the creatures which share this planet with us.

Seeing these kinds of things, both in person and through various media formats, provides a sense of escapism and serenity for me. B

ut it’s also what this represents – healthy and more diverse ecosystems that are intact and contain top predators are more resilient and provide better ecosystem services (like water filtration, cleaner air, climate regulation, disease regulation and nutrient cycling). These have never been more important than today, as the impact humans have on the natural world continues to grow.

And here’s the flipside. For people who care deeply about nature, such as myself, there is real anxiety about what humans are doing to the world.

This is concerning on an existential level as climate change is challenging the very lifeblood of our planet. But it is also a mental health issue on the biggest scale – climate change related events such as droughts, flooding, rising sea levels and other natural disasters all have significant mental health impacts (alongside physical ones too).

And the Covid-19 pandemic, arguably caused by human encroachment upon the natural world and the exploitation of nature, will have lasting mental health impacts that go far beyond the virus itself as we face economic hardship and ongoing disruption to social and support frameworks.

A glimmer of hope

So, we have this growing understanding of how nature impacts our mental health – but where do we go from here?

I am always hesitant to turn to economics when discussing nature (I think it misses the point) but it is an undeniable fact that mental health is a major cost to global economies (in England, it is estimated that poor mental health carries an economic and social cost of £105 billion a year). And it is also true that money is what drives change.

If we know that the mental health of a population can be improved and protected through access to nature, and that providing access to nature does not have to be massively expensive, then there is definitely an economic argument to be made with regards to lessening the burden on health and related services.

When this is coupled with the rising mental health cost of environmental degradation, it is easy to see how preserving nature can also preserve economies, as well as pay dividends for citizens.

On a smaller scale, we need to start considering how to allow greater access to nature for all people – not as a luxury, but as a human right.

Solutions to this will only be found through working across disciplines and involving mental health researchers, architects, national authorities, local authorities and many more. Holistic problems require holistic solutions.

But next time I am feeling particularly low, or suffering from a bout of mental health difficulties, I will try to remember that nature is an evidence-based, and for some an accessible method of alleviating some of these symptoms.

I will head to a park near me, lie down, close my eyes, take a deep breath, and do my best to soak among the trees…