Hear young people & the Agency project team discuss their tips & experiences for having better mental health conversations in our new podcast

For young people struggling with their mental health, those early conversations with practitioners can change everything.

For some, they can even be ‘make or break’, meaning the difference between a young person getting the support that they need, or never seeking help again.

That’s why giving them a sense of agency – the capacity to act independently and make their own choices – during these interactions is so vital.

Plus, it’s been shown time and time again that feeling empowered in this way can make a huge impact on improving outcomes for people on their mental health journey.

The Agency project

This is what our Young People’s Network found while working on the Agency project, which is all about young people’s sense of social agency.

During the project, the team got permission to watch real-life mental healthcare encounters involving young people, and analysed the verbal and non-verbal communication. They used this to examine how young people’s sense of agency is encouraged or hindered in these encounters.

The team came up with the concept of the ‘Agential Stance’ to describe a way of interacting that helps create agency – and therefore better outcomes – for young people.

There are 5 key steps to the Agential Stance. These are: Validation; legitimisation; avoidance of objectification; affirmation of ability to contribute to change; and involvement in decision making. We’ll go into these more below.

As the project draws to a close, we’ve created a podcast based on the stance – you can listen here.

In the episode, young people from the project’s YPAG (Young Person’s Advisory Group) with lived experience of mental health issues, talk to members of the project team about their experiences. They also share their top tips on how to improve the support that young people receive, based on these five steps of the Agential Stance.

Young people described validating experiences they had as positive, even if they weren’t given a solution at the end of the session.”

Creating agency with the ‘Agential ladder’

It might seem like quite an abstract idea, but picture the Agential Stance as a ladder, with each of the five points building on the previous ones. Together, they help promote and protect the young person’s sense of agency during the interaction.

The podcast goes through each of the five steps in more detail. Before we jump into that though, we’ll give a quick overview of what each step means in this context, so you have the definition to hand as you listen.

There is no one solution to a lot of stuff and so just to have someone hear you can change your whole…day and week and life.

The 5 steps explained

The five steps are a bit of a tongue-twister, but they all boil down to quite simple concepts.

As mentioned, these will be explained in the podcast, and discussed in more detail, but we’ve created five ‘explainer’ images to give you a quick introduction and some example phrases you could consider using.

- Validation

- Legitimisation

- Avoidance of objectification

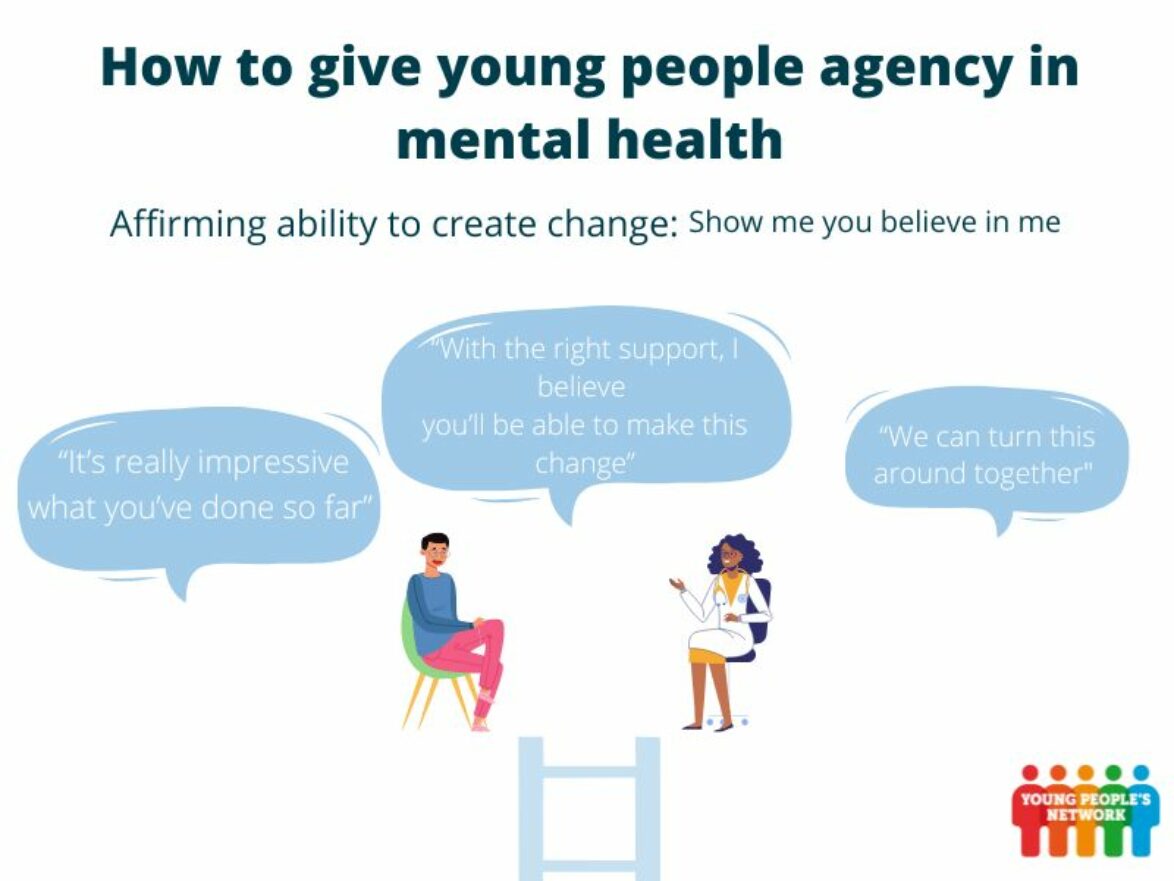

- Affirmation of ability to contribute to change

- Involvement in decision making

I think some professionals forget how much power they have over young people because all of us are trying to navigate what’s going on.

Listen to young people & the team share their thoughts

The project found that using these steps can make a huge difference when interacting with young people, which not only makes practitioners’ lives easier, it makes young people feel better and more empowered during a tough, and formative, time in their lives.

So, pop the podcast in your ears, or if you’d prefer, read the transcript below.

Some of the young people draw from their own experiences in this podcast. Please be advised that the content may be distressing for some.

Listen to the episode in full here, or wherever you get your podcasts.

How to give young people agency in mental health

We’ll also add the recording of an event where the Agential Stance is discussed to our YouTube channel and on this page when it’s available.

Stay up to date

Stay up to date with the project on the Agency website and with McPin’s work by signing up to our newsletter

Agency Podcast – transcript

For young people struggling with their mental health, those early conversations with practitioners can change everything.

For some, they can even be ‘make or break’, meaning the difference between a young person getting the support that they need, or never seeking help again.

Intro

I’m Rachel, and I work at mental health research charity the McPin Foundation. I lead our young people’s network, where we involve young people aged 13-25 in a range of mental health research projects and activity.

The way we usually do this is by setting up a young people’s advisory group – or what we call, a YPAG – to offer their input on how a project should be carried out.

YPAGS are typically formed of young people with direct experience of what the research is about.

Intro – Agency project

And that’s what we did here, with the Agency project, which explores young people’s sense of agency during mental health interactions.

If a young person has agency, it means they can act independently and make their own choices. When young people approach professionals about their mental health, it also plays a crucial role in whether those young people feel helped or harmed by that professional.

The professionals can either encourage or discourage the young person’s sense of agency, and this comes with various consequences.

Intro – podcast

We want to use this podcast as an opportunity to tell you about what we’ve learned. We think this could help practitioners during their encounters with young people. We really believe that, if professionals apply these learnings, then they are giving the young person the best possible chance on their recovery journey.

To get a glimpse of what happens between health care professionals and young people, we got permission to watch footage of young people in emergency departments who were seeking support during a crisis. We took note of how the professional interacted with the young person, both verbally and through body language.

We all took a lot away from watching this footage, even though at times it was really difficult.

We’ve shared some tips about how to improve the support that young people receive, based on our 5-point ladder called the Agential Stance.

Picture the agential stance as a ladder, with each of the five points building on the previous ones. Together, they help promote and protect the young person’s sense of agency during the interaction.

The five points are a bit of a tongue twister when you say them all together but don’t worry, we’ll go through each in turn. They are: validation, legitimisation, avoidance of objectification, affirmation of ability to contribute to change and finally, involvement in decision making.

During the podcast you’ll hear directly from our Young People’s advisory group, as well as several of our project leads, who are academics across philosophy, ethics, psychology, as well as clinicians. They all share their own reflections, all interviewed by Katherine, a member of our McPin comms team.

Some of the young people draw from their own experiences in this podcast. Please be advised that the content may be distressing for some.

First segment – Validation

When a young person first seeks support, the professional should show them that they’re listening, that the young person’s experiences are important, and that their experiences really matter. We call this validation.

To get us started, Katherine asked McPin team member Rosie, academic psychiatrist Matthew Broome and young person Catherine why validation is so powerful.

–

Rosie: I think, especially as a young person, you don’t feel like your feelings are valid, or if you don’t fully understand what you’re going through, you might not feel valid in the first place.

But also just like to have someone believe you. I remember when I was like 14, I went to the GP, I said, look, I think have an eating disorder, I don’t know what’s wrong with me and like, it was really important that they heard me. I mean, they kind of heard me, but it was also kind of like that whole, like, you need to get to a certain point to be able to be considered ill and all of that, which was really unhelpful and that kind of like invalidated my experience.

I know a lot of people like have gone with like self-harm stuff and people have kind of said, I could be treating someone who’s got a real problem or whatever, like I’ve had experiences where it’s like, oh, you’re a mental health patient – their whole tone changes.

That makes me feel like my pain and my reality is not real or valid – it creates like a, more of a distance between you and the practitioner and if someone’s validating you, you feel like, we can work together, you’re hearing me, you’re understanding me, you’re accepting what I’m saying.

I understand, like sometimes they have to ask difficult questions or get you to like, think about things differently but I think in so many walks of life, validation’s important and hearing what someone’s like lived experience is, whether that’s racism, mental health – for people to just sit there technically in a position of privilege where you have the say on what’s going to happen to me. I’m in a position where I’m trying to ask for help and for you to just say like, oh, that’s not what’s happening, it makes you feel even worse than you already do.

I think it can even just be little things. Like I have a GP that I feel like I can go to, because I know that she’s going to look at me in my eyes and she’s going to listen to what I’m saying and she’s going to say, I understand that must be really hard, and like, give me that feedback.

Matthew: And I guess just to respond to that, a few things you mentioned did resonate with the interviews we are watching with the young person’s group and with the research team where quite often we saw A&E consultations which almost felt like a kind of courtroom, where there’s this kind of, you don’t seem to be depressed or there doesn’t seem to be a suicidal crisis here.

And they kind of bring evidence and argue about, well, you look well-dressed or you’re smiling in the waiting room, or you’ve got plans to go out this evening.

I think the first step we see from the young people we were working with is that this initial validation is incredibly important to feel, as you say, there’s some kind of connection or bond between you and the practitioner and there’s that kind of curiosity and recognition of the suffering and distress that’s going on.

Catherine: For me I realized validation is super important because as human beings, we need to feel heard. We need to feel like we’re a part of something. And when somebody kind of dismisses us or dismisses the reality that we’re experiencing, it makes us feel invisible and that we’re not connecting or we’re not being seen. Our existence isn’t being valued.

And another thing that I find is that sometimes people can validate to a certain extent, but they’ll compare experiences. So it’s like what I went through isn’t as bad. And then somebody else would try and compare their own trauma with my trauma and try to make me feel worse for feeling the way I felt, because they felt that what they’ve gone through is heavier and they have more reason to be suffering.

And I feel like sometimes when people say, oh, if I went through this experience and I got out of it, then you should be able to do that too. But I’ve never really related to that because we don’t necessarily come from the same maybe cultural background, religious background, we don’t have the same genes. The way everyone’s brains work is very different.

Matthew: And certainly, again, from the young people who are involved now in our research, they emphasized ideas of curiosity, ideas of compassion, of allowing space to happen and that does take time.

Katherine: Yeah, one of the things I found so interesting when I was reading about this study was that young people described validating experiences they had as positive, even if they weren’t given a solution at the end of the session.

Rosie: I guess it’s probably our own awareness that, okay, the services are stretched, like there’s not a lot of time, we’re already probably quite sensitive to that. Like I definitely feel like, oh my gosh, they’re looking at their watch. Like, it’s just feeling heard and feeling like you’re not just a number.

I think for me personally, I’d rather that they just hear you and there is no like one solution to a lot of stuff and so just to have someone hear you can change your whole week or like a few days, or even like an hour of your day, like, okay, that person listened to me.

And especially when you’ve got a job like that, where you’re listening to people’s pain constantly, like it I’m sure is hard, but at the same time, it’s like, when it really counts, make sure you have a coffee or whatever, because that, that can change someone’s whole day and like week and life.

Matthew: But I think a skilled practitioners should try to begin to weave those two things together where possible, and offer something individualistic. And as you said, allowing time, compassion, curiosity, and certainly believe whatever the young person says.

And also, again, it came up in some of the discussions with young people about the link between validation and gatekeeping. That you know, being believed is also a route to extra resources or support. And that can be as simple as, you know, psychotherapy or medication, but also could be things like benefits, admission, so I think there are those important factors that professionals can bring to bear sometimes.

Second segment – Legitimisation

Once the young person feels validated, it’s really important that the professional legitimises their concerns. In other words, the young person should feel like they have made the right choice in seeking help, and that they have come to the right place to get it.

In this interview, Katherine speaks to young people Niamh and Carmen, along with Research Fellow Clara Bergen. They discuss whether it’s possible to ask the hard questions that practitioners sometimes need to ask, while still legitimising someone.

–

Niamh: So my experience of CBT, I had a bad experience with it and he was very much, he always put it on me. He didn’t lead a conversation. It was always how I led it. And it was, do you think you did the right thing? Is this the kind of treatment you think you should have gone for?

And that’s not what I needed to hear. I don’t know every type of therapy. I don’t know. I need him to tell me and help me out. So in that instance, he went too far the other way, which I think we see a lot of.

Like I think the tone of the voice makes a very big difference as well. So I found him quite patronizing. And as well, I think, it is important for him or her to ask probing questions, but it is also their job to make you feel comfortable in that environment and make you feel like whether it might be the wrong kind of support or the right kind of support that it’s good that you’ve even seeked help in the first place.

So it’d be nice to have had that you’ve done the right thing in seeking help, now let’s work together to see if this is the right support for you.

Carmen: I think also it’s such a big thing to ask for help in the first place and to sort of acknowledge you need that help is quite a big step for a lot of people. And then to make that step and then be told almost, you shouldn’t be here or why are you here if you’re not willing to cooperate what we’re offering, it’s sort of a kick in the teeth.

And I am grateful for the support that they can offer. However, sort of doing half a job rather than completing the job and actually trying to see someone through to the end of, whether it’s a temporary struggle or whether it’s a more permanent thing, you’re then creating either more problems or you’re prolonging that period of trying to recover, which in turn then creates more stress and it’s then a case of just going back or more waiting lists, waiting again after waiting God knows how long as it is, because I’m currently on a waiting list and it’s two years and I’ve been told I can’t get the support really until I get to that point, and I get the diagnosis.

Katherine: Yeah. That’s really tough to have a really long wait and then to be not necessarily sure that you’ll kind of get the support that you need once you get there. If you were to summarize what the difference between feeling legitimized and feeling de-legitimized can have on you when you’re interacting with a practitioner, what kind of difference do you think that makes?

Niamh: I think it makes all the difference, because when you’re not getting anything back or you’re being made to feel small, then I think you think I just can’t be bothered. I just don’t want to talk to this person anymore.

Whereas if you’re being legitimized and you’re getting the complete opposite, then you’re willing to open up and talk. So I think it’s a massive difference between opening up and sharing how you’re feeling and what’s going on, or completely closing yourself off and perhaps even damaging your mental health forever.

Carmen: I think some professionals forget how much power they have over young people because all of us are trying to navigate what’s going on. And then when you’re having these sort of additional struggles on top, it makes everything so much more difficult.

So there are some instances where I think it’s useful to be told, what options are available and to have that reassurance, that what you’re going through is almost quite a normal thing, but then there’s the sort of flip side of things where, okay, this, the young person still needs to have some control over what they’re doing.

Clara: It’s interesting because a lot of times it’s done through questions and I think a lot of times practitioners are trained to ask questions like what other type of service do you think would help you? What else can we do for you?

And I believe that those questions are trained in, so practitioners are kind of told to ask these questions, but if they’re asked with the wrong tone of voice, if they’re asked at the wrong moment in the assessment, they really come across as, you know, we don’t know what we can do for you.

One thing that we’ve looked at in the videos is just how frequently delegitimization is done through questions. So, you know, asking questions that might sort of show doubt about whether the person is telling the truth or whether their symptoms are as bad as they say, or things like that can, even if they’re very subtle and it’s, you know, if the practitioner might be trying to, for example, do a risk assessment or something like that, a lot of times it’s actually those questions that are coming across as de-legitimizing.

Carmen: I agree with what Clara said. And I think one of the big takeaways should be just for practitioners to be aware of how much power they have over someone. And especially a young person seeking out help from a service because we don’t really know what we’re doing and we’re expecting someone to guide us.

But if we’re being told either this guidance is wrong or be being given the wrong guidance, then you’re potentially creating a whole lot of other problems that then needs more help to sort of pick apart. And I don’t think all practitioners realized just how much impact they have on us and how vulnerable we are at the time.

Third segment – Avoidance of Objectification

Validation and legitimisation are both really positive ways to interact with young people, but sometimes being aware of what’s not helping is just as important.

Avoiding objectifying young people is vital. Objectification is what happens when a person’s opinions and feelings are not taken into account.

They are placed into a category and seen as a problem to solve – this could be viewing them through the lens of a particular diagnosis, or gender, or anything else that stops them being seen as a whole person with their own circumstances, thoughts and desires.

Here to tell us why it’s so important to avoid objectification, we have young people Carmen and Catherine, plus psychology researcher Michael Larkin from Aston University – starting with some ways objectification can happen.

–

Carmen: I think you tend to find it probably going into a mental health assessment that you have these professionals around you who are trying to almost fit you into a box to treat you rather than taking a more holistic approach.

So instead of maybe dealing with all the issues that someone’s facing, you end up dealing with just particular aspects. So although you might solve an issue in one area, you actually potentially creating other problems in other areas.

I think it tends to happen a lot when people are sometimes in crisis, because they’re just trying to almost find a quick fix and think, okay, what can we do at this immediate moment that could offer some sort of relief, rather than maybe just taking like that little bit of extra time to talk to someone, to actually fully understand the picture and what’s going on.

Michael: I think it’s something that happens to us a lot in life, isn’t it, that we find ourselves being treated as if we were a typical example of a familiar category.

We’re aware that people maybe have jumped to assumptions about us, and that they maybe think that we’re there for reasons other than the ones we want to talk about and it happens in all kinds of interactions with all kinds of professionals, but what’s really important about these ones is that you’re in a situation where the person seeking help is in a lot of distress. They’ve probably got quite a lot of complex things that they want to communicate and a situation that they want to be understood and getting it wrong has got fairly serious consequences in terms of, you know, the pathway from that first bit of the interaction.

It certainly feels sometimes as if the people seeking help in the videos we’ve been watching are sort of making an offer, you know, they’re sort of willing to share something. And then when what’s reflected back at them, doesn’t really match up they sort of retreat.

Catherine: I feel like when you have a professional in front of you and they’re using a lot of jargon that you’re not familiar with, and they’re talking about, I dunno, serotonin or things to do with your nerve receptors and da da da, they might not understand what all that means.

I’d also like to add that I don’t think someone being labeled is like, I wouldn’t say it’s all negative. I feel like as human beings, that’s how a brain works. We see a tree like, oh, the leaves, and then the branches, we know that’s a tree. It’s just how we label things we need, or then everything’s just going to be jumbled up and confused.

I think it’s just labeling, but also having room to explore. It’s like given the options this might be what’s going on, but there should be some flexibility in like maybe in the diagnosis of a patient.

Michael: So I think a good start would be trying to say, I understand why you’re worried. And saying something that shows and reflects what you’ve heard and about why the person is worried and saying, I’m glad you’ve come here to seek help. You know, you’ve done the right thing by coming to see us. We’ve seen one or two examples of that and it makes such a difference it’s really positive.

Carmen: I feel like it’s very easy going into an assessment for them once you start saying a couple of words, they almost start labeling you then, and then they start giving you this diagnosis and then they can start throwing things at you almost to enhance their thoughts.

So once they’ve got this preconception, it’s quite hard to shift or then to think more holistically about, okay, what other issues could be coming into play here? Is it definitely this or could that potentially be other influences?

Catherine: It depends to the degree, the severity of what mental health issues that young person is dealing with. I think that’s how a healthcare professional can assess, I guess, how much agency they can give. And sometimes, unfortunately, like a healthcare provider will have to diagnose someone as quickly as possible in order to not cause further harm.

Michael: In some of the interactions practitioners have said what would you like us to do for you today? Which is potentially a really good question, but it’s only a good question if you’re a person who’s navigated this kind of service before. But if you’re seeking help for the first time, you need a conversation about what the options are, you don’t know what’s possible.

I think sometimes assumptions are made in this kind of objectification that we’ve been talking about starts to have negative consequences in the way that the person is referred on or advised about what to do next.

One example we’ve talked about a bit is a situation where there’s an assumption made that because the person has got a partner that that partner will therefore be able to take care of them.

There isn’t a conversation about what that relationship is like, whether the partner feels able to provide support to them. There’s just an assumption made that because the person seeking help does have a partner that therefore it’s okay to send them home because their partner will look after them.

It’s those kinds of things. It’s the kind of quickly putting the person into a category. This is someone who’s not on their own, therefore the risk is diminished. It’s those kinds of objectification that are potentially you know that they’re undermining the risk assessment, but they’re also, you know, undermining the sense that the person is being cared for and understood and listened to.

Carmen: To me, I think it’s just taking that extra time when having these conversations to try to fully understand someone’s situation before making assumptions and the impact of how that just little bit of extra time, whether that’s like another 10 minutes, whether it’s another two minutes, how that time can actually bring out so much more information.

Fourth segment – Affirmation of Ability to Contribute to Change

Four our penultimate point, we talk about affirmation of ability to contribute to change. In other words, treating young people like they are capable of being responsible of their choices and actions.

This is a fundamental part of Agency, but it’s also a complex one. While it can be empowering for professionals to acknowledge that young people are capable of responsibility, they also need to be wary of avoiding blaming young people for their problems.

To help us get the balance right, Katherine asks young person Catherine, McPin team member Rosie, and professor of philosophy Lisa Bortolotti from Birmingham University, why affirmation is such an important part of the process.

–

Lisa: I think actually the idea that we can contribute to what’s happened to us, maybe we have a part in what happened to us in the past, and we can change what is going to happen to us in the future is actually the core of the idea of agency. So being an agent is being able to intervene in the environment around you, social and physical environment, and being able to change things, to do things.

People who may be struggling and especially young people, I think the idea of agency, of being able to contribute, is almost like a double- edged sword, because in a way you want to maintain that hope, that idea that the person can and will get better because of their own resources. But you also want to make it very clear that they are not alone, that they can have support. And everybody at every stage of their lives needs support.

Rosie: Personally, I think that okay, at that point you might need help from professionals, but you’re the person that’s dealing with the issues long term and you’re the person that’s going to have to be able to be independent and like eventually deal with those issues independently.

So to feel like you don’t have any kind of control or like, if you don’t feel like you’re being affirmed and you’re being put in a position where you think, okay, I can actually change things myself, then you’re just gonna feel like you’re relying on medication or, you know, the people that are there helping you.

And obviously that can be quite a long process. I mean, I was in an inpatient unit for a year and a half. So like, at that point I didn’t feel like I had any control or I didn’t believe that like, okay, I can do this by myself.

But I think, yeah, even if you have to say it like 20 times or, you know, members of staff are like just believing in you, you get the sense that they think that you can do that by yourself, because I think if you feel like people are giving up on you, then it’s harder to want to change or believe that you can because you probably are starting off at a point where you don’t believe you can. And if the professionals are telling you that you probably can’t, then you know, you’re going to just not even try.

Lisa: What is interesting is that in the video d interactions that we watched between practitioners and young people, we’ve found both situations. So the situation where the practitioner is not treating the young person as someone who can contribute, and maybe more passive recipients of the practitioners wisdom or advice.

But also we saw another situation where the practitioners was actively blaming the young person for the situation in which they were in, for instance, not realizing the consequences of self-harm or blaming them for not considering the impact of their actions on other people.

And we thought there was really something unhelpful in the context of the encounter of interaction. First of all, I think agency is not something that we have in isolation from other people. The environment is what enables us to act. So if something bad happened to us in the past, it may be that we contributed to it, is possible, but we weren’t alone in creating that situation. And so we can never be thought to be entirely responsible for it.

And it’s not, I think, reasonable to expect a young person who is struggling to take into account everybody else’s feelings and needs before their own. That’s not what should happen in the encounter. In the encounter they should feel that they are taken care of, they are listened to, they’re validated, they’re legitimized in their need to seek help.

One video encounter that we watched, I think was a very good example of good practice. And in that situation, the young person had been in a quite deep crisis in the past and the practitioner praised the person for getting better, for hanging on – the very positive language, like you know, you should be proud of yourself , you came a long way, this kind of affirmation, and also it looked towards the future, but in a realistic, not overly optimistic way.

So they realize that the person might need help and support in the future still, but they gave the person hope that they would be able to manage more of their own health by themselves as well.

Catherine: So for me it would be about seeing me as a person, as opposed to just fixing the problem. And so in that sense, it’s like, I’m a whole person. I’m not just something that you just trying to medicate, sedate, or I don’t know, just put me into a box of like, okay, she’s got depression and she’s got anxiety, she’s got schizophrenia etc. I don’t want to be defined by my mental health issues.

Lisa: It’s important for, for the practitioner to recognize what has been achieved because for some young people, they might not even realize that they have done something quite amazing.

Rosie: Yeah, like in terms of acknowledging how far you’ve come sometimes I think it was almost like, oh, well, done that’s really good, or like something that just feels like it doesn’t mean anything, but if someone’s like, oh, how would you have dealt with something back then, or how would you deal with something now? You’ve been through these other things and you didn’t deal with it like that. It’s like, okay, that I can actually see.

Fifth segment – Involvement in Decision Making

The previous four steps aim to lay the groundwork, so that we can achieve the fifth and final step on the agential ladder: involvement in decision making.

It’s vital that young people are given the opportunity to provide their point of view when it comes to decisions about their mental health, and we know that treatment tends to be more effective when young people have a say in it. This involves working together with the professional to identify what treatment is best for them.

In our final interview, Katherine asks young people Nusaybah and Michele, and project lead Rose McCabe, a psychologist at City University of London, what difference involvement can make to outcomes for young people.

–

Michele: One example might be that young people are kind of privy to certain circumstances and their life at the practitioner is not.

So like a young person might have depression and insomnia and a practitioner might give them like sleep hygiene techniques to help them with their sleep because that could stabilize their mood. But that person could maybe be sharing a room with older siblings who sleep later than them and these are all really small factors that you might not think is really important, but it can really impact a young person’s treatment adherence and their overall outcomes in treatment.

Because I think if the practitioner isn’t asking these open-ended questions and asking the young person, how do you feel about the treatment? Do you think this will work for you? Are there barriers in your life that might affect adherence to this?

Then they might just make the assumption that, ‘oh, this patient is really resistant to treatment or they’re noncompliant’ and that can really negatively impact the young person’s mental health and treatment in the long-term.

Nusaybah: So I think it’s really important for young people to be involved in decision-making because young people are the experts when it comes to their own treatment.

And so I think it’s really important what we’ve been doing because you know, we’re young people, talking about young people. It’s not like, you know, these professionals who are like so much older, who are from a different generation, who may not have lived experienced themselves, talking about it and doing what they think is the best, which sometimes it might be but not all the time. And so I think having different opinions is really important because I think with more perspectives, you get a fuller picture and a better idea.

Rose: We hear from people again and again that the unintended consequences of a negative experience when somebody seeks help, does often mean that they don’t seek help in the future when they’re really unwell and they really, really need support.

And then, I think we know the, kind of all the evidence suggests that when practitioners are good communicators, that the people, their clients, are twice as likely to kind of be engaged in the treatment and follow their advice, even if they don’t necessarily agree with the advice.

Michele: You know, when a young person is asked about what they think of something they feel really respected. And I think when you’re meeting with a practitioner and they’re in this huge position of power and they ask you, Hey, what do you think about this? How do you feel? What are your concerns?

And they see them as real and valid, that can be such a validating and empowering experience. And I don’t think that’s done enough, but I think that is so critical in helping a young person have agency in their treatment.

I think it’s important for the practitioner to kind of walk into the assessment or the therapy room, seeing it as a collaboration.

Nusaybah: I guess that’s like two professionals coming together or two experts coming together because you’re an expert in your own experiences, and they’re an expert in the field and you can both come together to try and work through this and help you get better.

And I think that is something that would make a lot of young people feel empowered and I think for me and my personal experience where maybe, you know, a couple of minutes before we start, we just like have a quick chat about what we did over the weekend, even if it’s not directly related to the work that we’re doing and the treatment and obviously we don’t really know, like, you know, waste loads of time, just, you know, talking about the weather, but, I think it’s important the relationships to not just be about the treatment.

Rose: I was going to say that one of the things that people say to us most often and young people have in, in our YPAG meetings in this project, is not being taken seriously and not feeling believed.

I think one of the things that people say is they would prefer is to have a sense of the options available to them, rather than say, you know, this is what you’re going to have for your treatment. But say, we could look at option A, B and C, so laying them all out from the outset.

And what do you think of each of these options? And, you know, even though you think this would be a good one, what might be problematic about this for you in terms of actually implementing it?

And then finally just acknowledging and saying to people that we’re here to support you, you know, that just verbally saying that is so important to people and you can see people visibly kind of respond so positively to that kind of a statement and say, this can be difficult and it can be difficult to make these decisions, but you know, we’ll do it together. We’ll work through it together.

Another important thing that people say to us is some practitioners say, you know, some of my patients or my clients find this difficult, has that been difficult for you? So you almost give people permission. Because it’s really hard to go to the doctor, you know, we talked about the power relationship, it’s really hard to go and say, I haven’t been doing what you advised me to do.

So for a practitioner to say, has it been difficult? What’s been difficult? So you’re giving people permission to say it’s been difficult rather than people feel very hesitant about saying that unless they’re given permission to do.

Michele: I’m not sure if this is the case for everyone, but I think a misconception about young people being involved in decision-making is like, okay, well they definitely know what they want and they should tell us what they want right now, if not, what’s the point of having them be involved, right?

But, I think yeah, you shouldn’t pressure them to make a decision straight away. You should give them information and give them time and give them space, just like you would to an adult.

Summary

As our team have demonstrated, these conversations are so crucial to get right – especially at crisis point – and we hope that these tips will help lead to more productive interactions for everyone.

To recap, the five steps of the ladder are:

- Validation

- Legitimisation

- Avoidance of objectification

- Affirmation of ability to contribute to change

- And involvement in decision making

We’ve found that all these things together help young people feel heard, and lead to better outcomes for their mental health.

We hope you’ve found this useful and can find ways to put it into practice in your daily interactions with young people.

Outro

If you’re keen to find out more you can head to our agency project website, agencyinmentalhealth.co.uk, or if you’re a young person and you’re keen to get involved with projects like this, take a look at our Young People’s Network.

You can also follow us on twitter at @McPinYPNetwork to stay up to date with our latest news and involvement opportunities.

Last but not least, a massive thank you to the young people’s advisory group and to the project team for getting involved in the podcast. It’s been so amazing to work with you all. I’m so excited to see what’s next for our team, as the project develops!

Work with us

We are always excited to hear from others who want to collaborate on mental health research. From delivering peer research to helping you with public involvement strategies and providing training, get in touch to chat.